Tags :: History

Trying to reach the sublime: Robert Eggers, cinematic poet of the past

In the Viking epic The Northman, the arthouse horror auteur behind The Witch and The Lighthouse takes on his most ambitious challenge to date.

![The Irishman [video]](/uploads/articles/irishman.jpeg)

The Irishman [video] (2019)

Robert De Niro, Al Pacino and Joe Pesci star in Martin Scorsese’s decade-spanning gangland opus, which turns out to be a very different movie than it seems … but you have to stick with it.

A Hidden Life (2019)

An ecstatic, anguished three-hour cinematic hymn, Terrence Malick’s A Hidden Life sings the life and death of Blessed Franz Jägerstätter in asymmetrical binary form, in contrasting theologies — theology and anti-theology — of the body.

Harriet (2019)

The strongest scene in Kasi Lemmons’ Harriet might be a moment when its indomitable protagonist appears at her weakest.

First Man (2018)

First Man is Damien Chazelle’s third film in a row about special individuals whose quest to achieve great things is linked to emotional isolation from others.

Operation Finale (2018)

It was the experience of reporting in Jerusalem on the 1961 Adolf Eichmann trial for The New Yorker that led the philosopher Hannah Arendt to coin her famous phrase “the banality of evil.”

Jeannette: The Childhood of Joan of Arc (2018)

Jeannette is a dialogue, and a mutual cross-examination, not only among the main characters of the drama, and above all between man and God, but also between the poet Péguy and the filmmaker Dumont, and even between Péguy the Socialist unbeliever of 1897 and Péguy the believing Catholic of 1910.

![Mudbound [video]](/uploads/articles/mudbound.jpeg)

Mudbound [video] (2017)

The more firmly rooted in a sense of time and place a film is, the more revelatory it often is of the present.

Detroit (2017)

Kathryn Bigelow’s Detroit has an important story to tell, but what story is it?

Dunkirk (2017)

Dunkirk is the first film Christopher Nolan has made that feels bigger than the director’s preoccupations and obsessions.

Grand Illusion (1937)

Asked what he was trying to do in Rules, Renoir is reported to have said, “I don’t care.” With Grand Illusion, it may not be much easier to say what he’s trying to accomplish, but there is no doubt that he cares.

Silence (2016)

When 17th-century Japanese authorities in the time of the Tokugawa shogunate found it necessary to send the colonial powers of Europe packing and their European Jesus with them, they didn’t just shatter the missionaries’ bodies. They shattered their narrative.

Hacksaw Ridge (2016)

Gibson crafts a resolutely traditional exercise in Hollywood mythmaking: a tale of a man who stoically endures accusations of cowardice before being vindicated as the bravest of all, a man of integrity who stands by his unpopular principles regardless of the consequences; a pious man whose sincere faith eventually wins the respect and admiration of his less devout comrades.

The Birth of a Nation (2016)

The prominent, polyvalent exploration of the uses of religion and especially Scripture, both to condone slavery and to condemn it, to sedate slaves and to inflame them, is one of the most striking and welcome things about the film.

The Innocents (2016)

The Innocents opens in a Benedictine convent in Poland in 1945, shortly after the event known, not without bitter irony, as the liberation of Poland by the Soviet army.

Spotlight (2015)

We cloak the monstrous in euphemisms. We call it “unspeakable” or “unthinkable” — designations that are accurate simply because in using them we make them so. In Catholic circles a dozen years ago, one sometimes heard about “The Crisis”; later it became “The Scandal.” We all knew what these terms referred to, but did we really know?

The priest, the student, and the swastika

Both films revolve around a number of tense cat-and-mouse interviews between the believing protagonist and a shrewd Nazi antagonist … The interviews in both films are a clash of worldviews.

The Train: When is art worth dying for?

Are manmade things ever worth dying for? How do you weigh the value of art or artifacts against the value of human life? On the one hand, human life is sacred; things are just things. On the other, the cultural heritage of a people is an irreplaceable treasure that belongs not only to the whole community, but to all future generations.

Becoming Saint Óscar Romero

The recent beatification of Óscar Romero, Archbishop of San Salvador from 1977 until his assassination in 1980, has drawn new attention to the gap between public perception and reality regarding this popular but controverted figure in El Salvador’s turbulent history. For those interested in beginning to understand who Blessed Archbishop Romero really was, the Christopher Award–winning 1989 film Romero, starring Raúl Juliá, isn’t a bad place to start.

The staying power of Selma

Long after other Best Picture nominees of 2014 have been forgotten, Ava DuVernay’s Selma, starring David Oyelowo as Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., will still be watched, appreciated and talked about.

The truth behind one of Netflix’s most popular shows

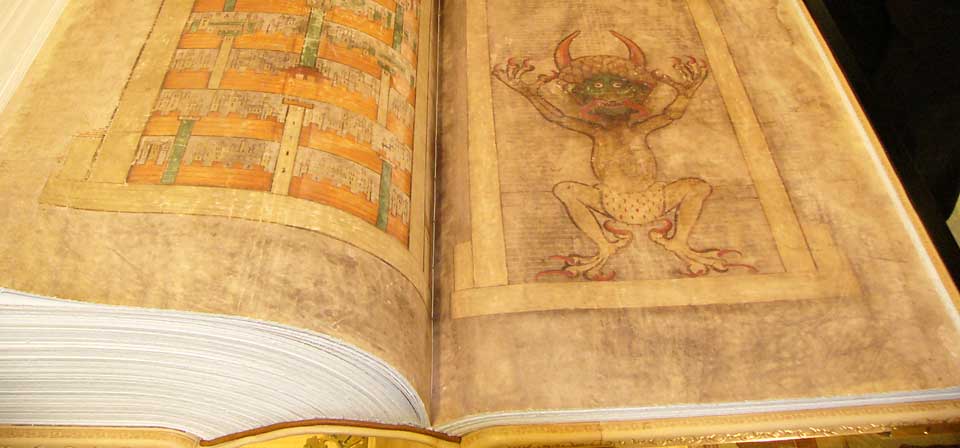

Want to know the truth behind the “Devil’s Bible”? Or the Dead Sea Scrolls? How about one of the Old Testament’s two famous arks? Curious about UFOs, Bigfoot or the Bermuda Triangle?

![Selma [video]](/uploads/articles/selma_pZAWhQ9.jpg)

Selma [video]

Very few historical films so successfully deconstruct the Great Man view of history while nevertheless offering a credible portrait of a leader who was, in fact, a great man.

Interview: Selma Actor David Oyelowo on Playing Martin Luther King Jr.

If an actor in a faith-based indie like Son of God told you he felt God had told him he was meant to play the role in question, you might not bat an eye. It’s more striking to hear such a thing from the star of a $20-million Hollywood film like the civil-rights drama Selma.

Selma (2014)

Selma achieves something few historical films do: It captures a sense of events unfolding in the present tense, in a political and cultural climate as complex, multifaceted and undetermined as the times we live in.

Unbroken (2014)

Angelina Jolie’s Unbroken is an honorable movie about an inspiring true story. It is impeccably crafted, with a raft of remarkably talented people behind it. It is a celebration of the old-fashioned virtues of duty, grit, fortitude and honor. In the end, it tips its hat to faith, forgiveness and reconciliation. The film I just described is a film that, on paper, I should love.

![The Theory of Everything [video]](/uploads/articles/theoryofeverything.jpeg)

The Theory of Everything [video] (2014)

Stephen Hawking and Jane Wilde’s 30-year-marriage gets the Wikipedia treatment, if Wikipedia were prettier, and sanitized.

From the Crusades to Columbus: Religion in Ridley Scott’s Historical Epics

A self-described atheist, Sir Ridley Scott has developed a generally bleak vision of religion, particularly the Judeo-Christian tradition, throughout his work, above all in historical sagas like Robin Hood (2010) and 1492: Conquest of Paradise (1992).

12 Years a Slave (2013)

What if I were to tell you that there has never until now been a major historical motion picture about the slave experience in America? Could that possibly be true?

The Untold Story of Slavery? Why 12 Years a Slave is Essential

I can’t believe I never realized it until now, but I can’t think of another fact-based motion picture about the slave experience in America — that is, a movie about slavery in the United States told from the point of view of actual, historical slaves, many of whose stories were published by abotionists prior to the Civil War and by civil rights activists after it.

42 [video]

42 in 60 seconds: my “Reel Faith” review.

Hyde Park on Hudson [video]

Hyde Park on Hudson in 60 seconds: my “Reel Faith” review.

Lincoln (2012)

Steven Spielberg’s masterful Lincoln might more accurately have been called The 13th Amendment — and while the choice of the more marketable title is easy to understand, the more crucial decision to limit the scope of the film to the last few months of Lincoln’s life, and to focus less on Lincoln himself than on the political machinations of bringing about his most enduring legal legacy, must have been harder to make.

Argo (2012)

The fact-based premise is almost enough to sell Argo by itself. Argo opens and closes as a tense political spy caper, but it’s also an affectionate send-up of the movie-making process. The old advice to writers to “write what you know” is applicable to movies about movies, from Singin’ in the Rain to The Artist, and few subjects inspire Hollywood — or appeal to movie fans and film critics — more reliably than Hollywood itself.

For Greater Glory (2012)

For Greater Glory tells a story of religious freedom and oppression that is far too little known, and that would be important and worthwhile at any time, but is strikingly apropos in our cultural moment.

For Greater Glory [video]

For Greater Glory in 60 seconds: my “Reel Faith” review.

War Horse (2011)

In War Horse Spielberg harkens back to an earlier cinematic age, creating something more like a Golden Age Hollywood epic than any film I’ve seen in years, the one other notable example being Baz Luhrmann’s Australia.

J. Edgar (2011)

The life and work of J. Edgar Hoover offers grist for a dozen different movies or more, and Clint Eastwood’s J. Edgar wants to be all of them at once. It’s the sort of staidly respectable, competently directed biopic that gives a bad name to competently directed biopics, and possibly to respectability.

The Help (2011)

Based on Kathryn Stockett’s best-selling 2009 novel, The Help is largely about the daily humiliations and injustices to which black maids and nannies working in white homes were subject, and the invisibility of these humiliations to their white employers, until, in this fictional account, their stories are told, first in secret and then in public.

There Be Dragons [video]

If you don’t have 30 seconds to spare, here’s a spoiler: There aren’t really any dragons.

There Be Dragons (2011)

As played by English actor Charlie Cox (Stardust), Josemaría emerges as a likable, dedicated, virtuous young man much loved by his circle of friends, the first generation of Opus Dei. There are a few evocative scenes, such as the impression that a barefoot friar’s tracks in the snow make on the young Josemaría. Yet despite a line or two about Opus Dei spreading to other countries, there’s little sense of Escrivá himself as a figure of any particular note.

The Conspirator (2010)

Credibly researched by screenwriter James Solomon and beautifully filmed by Newton Thomas Sigel (The Usual Suspects, Three Kings, Valkryie), it’s a rare historical drama that credibly captures a sense of another era while allowing its characters to breathe and talk and argue like men and women living in the present tense.

Of Gods and Men (2010)

Xavier Beauvois’ sublime Of Gods and Men is that almost unheard-of film that you do not judge—it judges you. To one degree or another it defies every attempt to put it in a box, to reduce its challenge to a political or pious ideological stance to be affirmed or critiqued.

A History of Violence: Agora, Hypatia and Enlightenment Mythology

Alejandro Amenábar’s Agora is a work of hagiography, and, for that matter, of anti-hagiography. Among its burdens are that Hypatia of Alexandria, the celebrated neo-Platonic philosopher and mathematician, is worthy of veneration, and also that Cyril of Alexandria, saint and doctor of the Church, is not. Neither of these theses is without prima facie plausibility, or unworthy of serious-minded and nuanced exploration. Agora is serious-minded to a fault, but nuance, while not absent, is lacking.

Katyn: Poland’s Dark Night

Exactly 70 years ago today, on March 5, 1940, Josef Stalin and the entire Soviet Politburo signed an order to massacre tens of thousands of Polish prisoners of war: officers, mostly reservists; doctors, academics, civil servants, clergymen of all faiths—the cream of the Polish intelligentsia.

Roma, città aperta [Open City] (1945)

Developed in Rome during the Nazi occupation, shot in the Eternal City shortly after the Nazi withdrawal, Roberto Rossellini’s Rome Open City stunned audiences the world over who saw in it an unmediated authenticity more evocative of the documentary quality of wartime newsreels than of the artificiality of earlier, more conventional WWII dramas.

The Train (1964)

How do you weigh the cultural heritage of a nation against the value of human life? That’s the subtext of The Train, a wholly persuasive, intelligent thriller crisply directed by John Frankenheimer (The Manchurian Candidate) with documentary-like realism and emphasis on action and problem-solving.

In the Shadow of the Moon (2007)

Man’s own shadow, as much as the moon’s, lies across In the Shadow of the Moon, David Sington’s moving documentary of the U.S. Apollo program. An eloquent testament to the grandeur of creation as well as man’s unique place in it, In the Shadow of the Moon offers a remarkable look at the history and technology of the Apollo program, but an even more extraordinary glimpse of the men who lived it and made it happen.

Titanic (1997)

It kills me to say it, but give the devil his due: James Cameron is the king of the world.

World Trade Center (2006)

Where Paul Greengrass’s brilliant United 93 crafted a documentary-like anatomy of events without presuming to get inside people’s heads or explain actions or motivations, World Trade Center is a more conventional Hollywood film, with dramatic dialogue, characters following clearly plotted arcs, and a swelling soundtrack to reinforce the mood.

United 93 (2006)

Whatever monument is eventually built at Ground Zero or anywhere else, United 93 is as fitting and worthy a memorial to the victims and heroes of September 11 as one could hope for.

Sophie Scholl – The Final Days (2005)

Sophie Scholl is one of a very few films that accomplishes one of the rarest and most valuable of cinematic achievements: It makes heroic goodness not just admirable, but attractive and interesting.

Apollo 13 (1995)

In an age when we rely on computerized directions and GPS devices to drive to the next town, it seems an almost mythic scenario: brilliant men calculating outer-space trajectories on the fly with pencils and slide rules, keeping life and limb together literally with duct tape, flying to the moon and back simply because they could.

Judgment at Nuremberg (1961)

Downbeat, intelligent, and compelling, the film is brilliantly constructed and acted, bringing lucid, forceful moral argumentation as well as emotional sympathy to both sides without tipping its hand until the powerful climax. Tribunal justice Dan Hayward (Spencer Tracy) is the ideal foil for the film’s rhetoric: a self-deprecating, folksy American circuit court judge with no ax to grind and a winsome appreciation for his own obscurity, knowing he’s sitting in judgment of defendants no one else wanted to judge.

“I have a hard time making any decision whatsoever”

For German filmmaker Volker Schlöndorff, the appeal of making The Ninth Day, a fact-inspired film about a priest in a Nazi concentration camp who is briefly released, goes back over five decades to Schlöndorff’s film-club days at a Jesuit boarding school, where he first encountered Carl Dreyer’s silent masterpiece, The Passion of Joan of Arc.

The Ninth Day (2004)

The Ninth Day digs beyond rote charges of ecclesiastical complicity and counter-arguments to explore various levels of resistance and protest — and their consequences.

Hotel Rwanda (2004)

Not in the now-distant mythology of World War II, with the iconic evil of the Nazi regime pitted against the warriors of the Greatest Generation, or even the likes of larger-than-life Oskar Schindler. Here is a horror within living memory of nearly anyone old enough to watch the film, a holocaust without the cover of a massive bureaucratic machine or industrialized, sanitized gas chambers.

Schindler’s List (1993)

From the armbands to the ghettos, from forced labor to extermination camps and beyond, Schindler’s List covers the successive historical stages of the Final Solution more comprehensively than any other popular film had at the time, or has since. That, in part, is its great achievement — and, for many of its critics, its enduring stigma.

Grave of the Fireflies (1988)

A haunting, harrowing war movie, an emotionally devastating character study, and an extraordinarily restrained example of animé or Japanese animation, Grave of the Fireflies is a unique and unforgettable masterpiece.

Recent

- Crisis of meaning, part 3: What lies beyond the Spider-Verse?

- Crisis of meaning, part 2: The lie at the end of the MCU multiverse

- Crisis of Meaning on Infinite Earths, part 1: The multiverse and superhero movies

- Two things I wish George Miller had done differently in Furiosa: A Mad Max Saga

- Furiosa tells the story of a world (almost) without hope

Home Video

Copyright © 2000– Steven D. Greydanus. All rights reserved.