WALL•E (2008)

In a barren wasteland of endless towers and canyons of refuse, a single creature stirs: a small robot chugging tirelessly about, almost imperceptibly bringing order out of disorder.

His boxy body is a portable trash compactor into which he scoops load after load of the sea of trash stretching in all directions, producing cubes of compressed detritus which he neatly stacks in heaps growing to the scale of skyscrapers. He is the last of his kind, and “WALL‑E” (an acronym for Waste Allocation Load Lifter Earth-Class) is effectively his name as well as his make and model.

Caveat Spectator

Mild animated menace. (“Presto”: Looney Tunes–style slapstick.)WALL‑E has a job, but he also has a life… an inner life. He works with his body, but he lives with his mind. Amid the rubble he efficiently disposes of, WALL‑E finds oddments and curios worth salvaging: a hinged ring box, a plastic spork, a Zippo lighter. The pride and joy of his collection is an old VHS copy of Gene Kelly’s Hello, Dolly!, which wouldn’t be many people’s top choice for a desert island movie, but beggars can’t be choosers.

Actually, the naive enthusiasm of “Put On Your Sunday Best,” which WALL‑E plays obssessively while acting out Michael Crawford’s hoofing, ideally expresses the robot’s spirit of hopeful wonder — probably because he absorbed it from the film in the first place. Isolated for centuries amid the rubble of human waste, WALL‑E has become a wide-eyed romantic. Such is the ambivalent legacy of mankind in Pixar’s WALL‑E, directed by Andrew Stanton (Finding Nemo).

Without warning, WALL‑E’s world is shattered from outside by an event as incomprehensible and momentous as the appearance of the primordial monolith in 2001: A Space Odyssey. Awe, panic and ecstasy pull WALL‑E hugger-mugger in all directions at once. All is changed. The words of Dante catching his first glimpse of Beatrice apply: Incipit vita nova, “Here begins the new life.”

The new life is irrevocable; to go back to being no more than a salvager of curiosities and compactor of trash would be unthinkable. When, to his alarm, WALL‑E realizes it could come to that, he unhesitatingly turns his back on his whole world, risking everything for what he has found. Love has opened the universe to him, in all its splendor, terror and ugliness.

Although I suppose most readers will have seen at least the trailers if not the film, I recount the import of these events without mentioning specifics, in part because I figure viewers who know what happens don’t need me to tell them, and the few who don’t deserve a chance to see these scenes for the first time as I was lucky enough to, not knowing what was coming.

Beyond that, though, it’s the import, the effect, that is so striking, that is worth highlighting. Slapstick, adventure and love are all familiar elements in animated family films. Awe, existential themes and wholesale worldbuilding are not, at least in mainstream American animation. Even Pixar has never attempted anything on a canvas of this scale. From Monsters, Inc.’s corporate culture to Finding Nemo’s submarine suburbia, previous Pixar films have never strayed too far from the rhythms of real life. WALL‑E creates a world that, despite clear connections to contemporary culture, looks and feels nothing like life as we know it, with unprecedented dramatic and philosophical scope.

True, animation master Hayao Miyazaki has done all this and more, with vigorously imagined worlds as evocative and haunting as Tolkien’s Middle-earth. On the other hand, WALL‑E’s achievement is realized with fable-like simplicity, with little dialogue throughout and virtually none at all for the better part of the first hour. In addition to 2001, the nearly wordless first act recalls the childlike wonder of early Spielberg and the silent comedy of Chaplin, with WALL‑E’s blend of curious naivete and pathos at once reminiscent of E.T. and the Little Tramp. (WALL‑E’s “voice,” such as it is, is the work of sound designer Ben Burtt.)

As the story transitions from this magical beginning into the very different second act, in which we learn more about the fate of the human race as well as the cause of the earth’s sad status, it’s not immediately clear that the film will be able to live up to the perfection of the first act. In a sense it doesn’t quite, though continual invention, creative boldness and visual wonder keep the bar high.

One of the best bits involves WALL‑E’s quirky destabilizing effect on other robots he encounters, such as M‑O (Microbe Obliterator), a fastidious little ’bot determined to sterilize every surface grimy WALL‑E has marred. There’s also a lovely, balletic outer-space pas de deux between WALL‑E and EVE (Extra-terrestrial Vegetation Evaluator, voiced by Elissa Knight), the sleek probe droid with big blue eyes and a deadly draw.

Where WALL‑E’s lonely life on earth had a level of science-fiction realism to it, when we finally meet mankind WALL‑E turns broadly satirical, targeting mindless consumerism with Swiftian savage hyperbole. Now living in a corporate space cruiser, mankind has completely succumbed to the total lifestyle package of the all-powerful BuyNLarge (or BnL) corporation, degenerating into a grotesque parody of couch potato conformity so debilitating that the human spirit is effectively comatose.

Despite one touch with a reasonable sci-fi basis, this conceit doesn’t bear scrutiny. For one thing, the human spirit is pretty irrepressible; for another, a 100 percent couch-potato society wouldn’t be economically sustainable. As Swiftian satire, though, it’s a bold, vivid image. I’m reminded a little of the poem TeeVee by Eve Merriam:

In the house

of Mr and Mrs Spouse

he and she

would watch teevee

and never a word

between them spoken

until the day

the set was broken.Then “How do you do?”

said he to she,

“I don’t believe

that we’ve met yet.

Spouse is my name.

What’s yours?” he asked.“Why, mine’s the same!”

said she to he,

“Do you suppose that we could be…?”But the set came suddenly right about,

and so they never did find out.

In the person of the Captain (Jeff Garlin), WALL‑E does give mankind a chance to improve, a little, and to take some baby steps on the road to redemption. While I might have liked a more textured vision of humanity, ultimately the story belongs to the robots, especially WALL‑E and EVE.

While the film’s themes of consumerism and environmental carelessness are unmistakable, unduly political spin on the film is probably more related to election-year hypersensitivity than the film itself. WALL‑E is not about left or right, liberal or conservative. Rather, it is about living thoughtfully, about what traditional Christian language calls good stewardship of resources and the environment.

If the filmmakers demand a lot of themselves, they have high expectations of their audience too. As with Ratatouille, Pixar has decidedly not set out to make the most broadly audience-friendly film they could have. This isn’t Kung Fu Panda, or even Cars — not by a long shot.

Will kids sit for long stretches of visual and aural storytelling with little or no dialogue? Why not? As I write this review my three older kids are watching a silent Douglas Fairbanks swashbuckler on DVD. Will viewers be willing to immerse themselves in a story with bleak, oppressive surroundings, without familiar parent–child or other domestic relationship dynamics, without fuzzy protagonists, without familiar lessons about believing in yourself and so forth? Those who will will be rewarded with one of the most enthralling, exhilarating films in years.

P.S. The new short playing with WALL‑E, “Presto,” is as brilliantly hilarious as anything Pixar has done.

Related

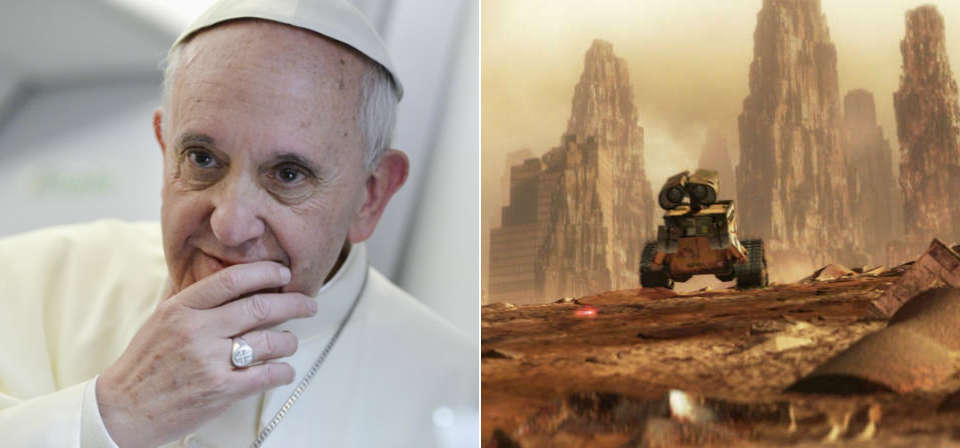

Pixar and the Pope: Pope Francis’ Laudato Si’ and Pixar’s Wall-E

“The earth, our home, is beginning to look more and more like an immense pile of filth,” Pope Francis writes. “In many parts of the planet, the elderly lament that once beautiful landscapes are now covered with rubbish” (LS 21). From the outset Wall-E looks as if it had been created with these words in mind, projecting them into a dystopian future in which rubbish has expanded to cover the entire planet, even surrounding the Earth in a halo of space debris.

RE: WALL•E

Link to this itemSteven, I just want to thank you for this site, for the time you take to analyze each movie. I love that your reviews are not the typical “air head” reviews but that you look for the more profound meaning of the movie and the morality in them. I had a chance to see you once in Life on the Rock commenting on Narnia (Lion, Witch and Wardrobe) and thanks to that I decided not to take my five-year-old to see it. Since then your site has been a must every time I want to take my children to the movies.

About WALL-E: I think it is a lovely movie; my kids (an eight-year-old and a four-year-old) loved it — they laughed, they got sad, they understood it perfectly. Never in the whole movie I heard a complaint about it being boring or long. After it was over my husband and I talked with them about our responsibility to take care of the world since it was a gift from God, and also about how we use our talents and our bodies and time to help everyone around us and be happy.

Thanks a lot again and God bless your apostolate.

RE: WALL•E

Link to this itemIn your article on 2008 family films you mentioned the possibility of Wall-E for Best Picture. I thought that the reason they created a “Best Animated Picture” category was to avoid having an animated film among the final nominees for Best Picture.

RE: WALL•E

Link to this itemI will admit that Pixar’s WALL-E is brilliant in a lot of ways. I still wouldn’t allow any child of mine to see it, though, because of the insidious and ridiculous anti-capitalist mentality it espouses. Of course, that’s exactly what will make the Academy vote for it. Which proves once again that Hollywood is the enemy of mankind.

RE: WALL•E

Link to this itemFunny, how different Wall-E appears to the people who are its target. Fat people are not “symbols of ultimate decadence” — we’re real, live, human beings worthy of respect. For most of us, Wall-E functions at the same level as a minstrel show, or some vaudeville about “piccaninnies.” The most overwhelming factor in the film is its bigotry and hatred-inducing propaganda directed at a minority group. And, yet, how few reviewers even seem to notice how devastatingly we’re hated and slandered. Your “ethics” score was a +1; mine’s -10.

Recent

- Crisis of meaning, part 3: What lies beyond the Spider-Verse?

- Crisis of meaning, part 2: The lie at the end of the MCU multiverse

- Crisis of Meaning on Infinite Earths, part 1: The multiverse and superhero movies

- Two things I wish George Miller had done differently in Furiosa: A Mad Max Saga

- Furiosa tells the story of a world (almost) without hope

Home Video

Copyright © 2000– Steven D. Greydanus. All rights reserved.